Off-Season Artists: Jan Wheeler

Just in time for the springy weather, we’ve got another Off-Season Artist! In this series Alex, who spends his time pacing the vaulted halls of the internet, head reverently bowed as his footsteps echo into digital eternity, interviews one of our artists to learn about their process and personality.

This week, it’s landscape painter Jan Wheeler!

So let’s get right into it. Your style is very difficult to pin down. Your landscapes are both very naturalistic but also otherworldly. There’s a monumentally static quality to your rocks and hills, but they all flow together in swirls and motion. How do you reconcile these seemingly competing elements so effectively?

Each piece sets out to share the rhythms and forces I’ve observed. There’s always an underlying rhythm, perhaps the strong winds of a storm, or a gently rippling breeze.

It’s that underlying rhythm that shapes the piece. Whether sky, water, rocks or hills, the wind flows over and sculpts all. Light and shadows from the skies flow over rocks and hills with the same force and rhythm. I work with all the elements together to create the choreography of the composition. The fluid lines and curving form draw the viewer’s eye smoothly through the piece so they too can feel the wind at play.

Who would you say were your influences in developing this style? It’s quite unlike a lot of other landscape painting out there.

A major influence for me was a contrary one: Cezanne. By that, I mean that while he explored planes of light and form in a landscape, I was aware of a curving form. I knew I had to diverge from his work to find a way to interpret what I was “seeing”. The artist I consider the key influence would be Henry Moore, whose tumbling, flowing forms enabled me to see how I could develop the flowing movement I was trying to capture.

Paul Cezanne, “La Mont Sainte-Victoire” and Henry Moore, “Reclining Figure”

Paul Cezanne, “La Mont Sainte-Victoire” and Henry Moore, “Reclining Figure”

Wow. Now that you mention it, I can really see that. I understand you also have a great deal of different regional influences. You’ve travelled quite a bit throughout the world—Japan, Saudi Arabia, the UK, Italy—and clearly you’ve used your diverse experiences to hone your style. What overseas experience would you say was the most valuable for making your art what it is today?

I would have to say that my time in London, UK was most valuable. I was able to study the works of many great artists and explore my own interpretation of landscape against that inspirational backdrop.

I played with the curving light and form of London’s plain trees and the rolling hills of the South Downs. During this time of development I worked in an office across from the Tate Gallery, with a Henry Moore sculpture in its front courtyard. His fluid, smooth forms draw the eye through and around the three-dimensional forms almost without awareness. Seeing his work in situ sent my mind racing through the possibilities of my own developing style by further exploring the fluid movement and rhythms of a landscape.

“Wind Sculpted Skies”

“Wind Sculpted Skies”

In spite of all that travel, more than any other subject the interaction between big Canadian waters and their skies seems to captivate your attention. I’m thinking of “Wind Sculpted Skies” in particular, one of your most ominous paintings and one of my favourites. What draws you to those subjects?

I’m drawn to the movement in landscape and want to capture a scene, not in its stillness, but in its living. Water and skies are rich with rhythm and simply captivating when observing. They’re a challenge for me with complex dramatic shifts that require complex choreography within the composition.

“Wind Sculpted Skies” is a scene from the shores of Lake Superior. The painting describes a long, age-worn rocky peninsula weathering once again the force of an expansive storm front. Strong winds drive and sculpt the sky, providing a rich choreography for me to work with.

There’s no place quite like Lake Superior, is there? On that note, you’ve done quite a bit of backpacking and canoeing. What’s your favourite natural space to get into in Canada, and why?

The north shore of Lake Superior never fails to inspire and challenge me. I’m captivated by the geologic forces in constant battle there, and on a scale that can be very hard to bring down to even a large canvas. Its geologic age gives it an underlying weight that resonates in the rhythms I observe.

For an artist who loves to work with stormy skies and turbulent water, the great lake provides me with a rich range of awe-inspiring moments.

“Break in the Storm”

“Break in the Storm”

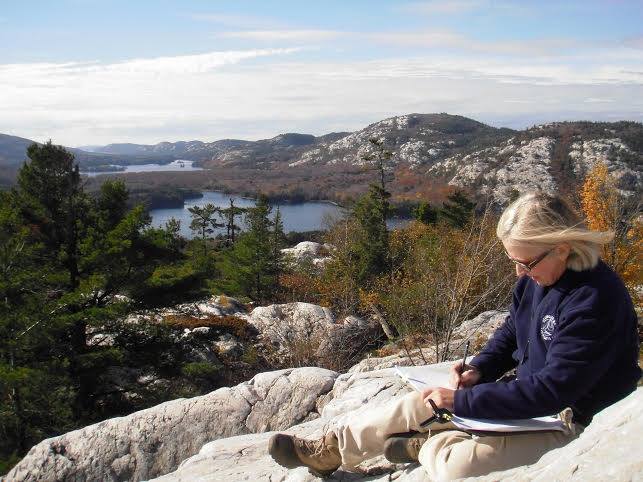

Speaking of getting out and working on pieces in the open air, one of the notable things about your paintings is their sheer size and ambition. When you’re in the presence of one, boy does it take over! What’s the process of going from mobile sketch to huge canvas like for you?

It’s great to hear that the paintings are connecting with you.

While on location I sketch, take photos and if I have colour with me, I’ll do a colour study for later reference. The scale and complexity of the scene usually dictates the scale of the final piece. The larger the scale of the scene and the more complex the underlying rhythms, the larger the final painting needs to be.

A final drawing precedes the painting, where I work out the rhythm in the landscape in a finished composition. This is important in order to have a consistent flow for the eye to follow; to draw the viewer into the underlying dance of the scene.

On canvas, I can develop the flowing scene more as the brush moves and blends the colour throughout the piece. The largest piece I’ve completed is a 48”x60”, which, if you know me, is as big as I am and that brings its own challenges. The extra work is worth it though as a larger canvas lets me develop and express more dramatic and complex scenes.

And last but not least, just for fun: what’s something we might not know about you?

Well, over the years I’ve had encounters with a lot of wildlife: a bobcat, fisher, weasels, elk, bears and many more. But probably the most memorable was when I was kissed by a camel in the Saudi desert.

I was with my husband and a group of friends, heading across flat sands to the Red Sea for some snorkelling when we came across a female camel and her two youngsters.

We stopped some distance away and watched quietly, taking pictures. The curious young camels playfully approached, soon followed by the mother. Everyone in my group backed up out of range, worried about an attack by the mother. I could see the mother wasn’t stressed and felt it best if I just stood quietly, making no moves.

The kids stopped before they reached me and looked on with curiosity but kept their distance. It was the mother who stepped up to me. She slowly, gently sniffed my face, my hair and then gently rubbed a cheek. She looked at me carefully one more time and then her incredibly long tongue washed my face in a big kiss. Astonished, yet careful not to move, I spoke to her quietly, thanking her, and watched as she and her kids went on their way.

That’s it for Jan Wheeler! She’s a delight and we can’t get enough of her art…

Check in soon for our next Off-Season Artists post!